This is a tribute to my father, Albert Georgijev, and dedicated to keeping his story alive.

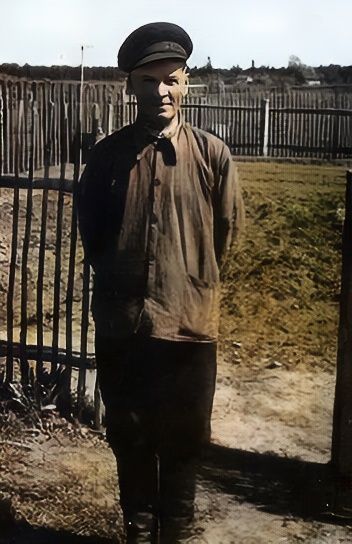

He was born in Russia 1924 in Niiskovitsa, a predominant Finnish village in the Ingria region near St Petersburg/Leningrad.

On week days Albert and Salme attended a Finnish elementary school and returned home for the weekends. Even though school was miles away they walked carrying provisions for four nights. On leaving school Albert worked with his father on their farm. For Albert, rural Ingria, had always been peaceful until Stalin introduced an agenda designed to divide communities.

First, a series of propaganda posters (by Getty) appeared inciting hostility against non-Russians. These visuals unequivocally blamed an upper peasant class (Kulaks) for the failure of plans to revolutionise industry and agriculture.

In rural communities orchestrated demonstrations demonised successful farmers, religious leaders, and non-Russians. In the Leningrad Oblast, Ingrian-Finns became a State target of hate.

The Stalinist solution was to remove these 'Kulaks'. It called for dekulakisation: the death of an entire class!

In the dark years that followed Albert witnessed at first hand the gross humiliation of his parents: Vassili and Aliide.

1930s: Life for the family is about to change. The full force of Stalin's Marxist agenda is about to decimate the Ingrian-Finnish villages west and north of St Petersburg. Aliide by this time had lost two of her children and with growing uncertainty about the future had to deal with the prospect of losing her home, and livelihood.

Aliide fell foul of the new Bolshevik order on two fronts: she was an Ingrian-Finn, a targeted non-Russian ethnic group, and she regularly attended church despite State enforced mandatory Atheism.

Aliide was in turn concerned for her parents, Madis and Maarja, given their large farm and status.

Madis and Maarja met in St Petersburg and married in 1884 in a Lutheran church. They lived temporarily in a converted sauna-haus in the Finnish village of Markuse whilst Madis built what my aunt Salme described as a 'fine house'.

Surplus dairy produce and horse-feed was taken to markets in Gatchina and St Petersburg and over time this became a relatively prosperous household.

Madis worked very long hours in the field although everyone helped on the farm. On marrying each child received some farmland.

As for Aleksander, his wife and two children left for Sweden to avoid the growing persecution of landowners.

Aliide was a skilled seamstress having trained in Narva, Estonia. She stayed with relatives and left vowing to return. She reminisced about Estonia and promised she would take the children there one day.

Being the proud owner of a sewing machine she provided a service of tailoring and repairing cloth.

Albert's father, Vassili Georgijev, was an orphan raised by a Finnish widow in Niiskovitsa village, Ingria. There is an absence of details regarding his background and the Bulgarian surname a mystery.

Vassili's farm ensured a degree of self-sufficiency in that he was able to feed his family on what he managed to produce.

Vassili owned about eight acres of land and this categorised him as a "Kulak".

Under Marxist guidelines Madis owned too much land.

Madis and Maarja were duly stripped of all they owned and ordered to be deported by train to Siberia. On the day they were due to be collected for the trip to Gatchina railway station they could not be found despite a search.

Madis and Maarja envisaged serious problems in surviving the journey to Siberia. They decided to not comply and to face the consequences.

The consequences, though, seemed lenient. Yes, they lost the farm and their home but they were exiled to nearby Volosova with strict limitations as to their movement. Despite the threats they made furtive visits to family.

Vassili, was judged to have too much land. His land and livestock were confiscated but the Georgijevs continued to live in the house, allotted a dairy cow and put to work as a labourer on the farm.

In 1931 family life became even more difficult for the family when the front part of their home was reappropriated as a 'collective' shop which sold farm produce and vodka. Despite a country-wide shortage of food collective shops were well stocked with State vodka. However, plentiful vodka, and access to the family's rooms compromised the safety of Aliide and her daughters.

When inebriated strangers barged into the house under the guise of the sewing machine being illegal an altercation ensued with Aliide and her children physically preventing its removal. During the same period (c.1938) school instruction in any language other than Russian was prohibited. At that point the education of Finnish speaking children ended. Knowing that Alide's parents' house in Markuse was vacant the family moved there and in the years that followed two more children, Lonni (Leontiina) and Maria, were born.

With the removal of farmers agricultural yields fell significantly. The State response was to make fields longer and mechanise further.

To elongate fields in Markuse the family were evicted and the house flattened. They loaded essentials onto a cart leaving what they couldn't carry. Opportunists gathered in the hope of salvaging items.

The family of seven relocated to a nearby barn for three weeks until a Finnish family accommodated them as best they could in a small house! My father remembered the experience of trying to find floor space to lay down.

Vassili found another home before the Winter of 1938. Three years later they moved 30km north to Vitino close to a Russian Air Force (VVS) base. Both Albert and Meeta found regular paid work at the base but within four months German bombers inflicted serious damage to the base.

To avoid the bombing the family left Vitino for the safety of nearby woodland. Vassili settled the family down alongside an embankment.

After a few days a Russian patrol discovered them and ordered them to move out of the woods.

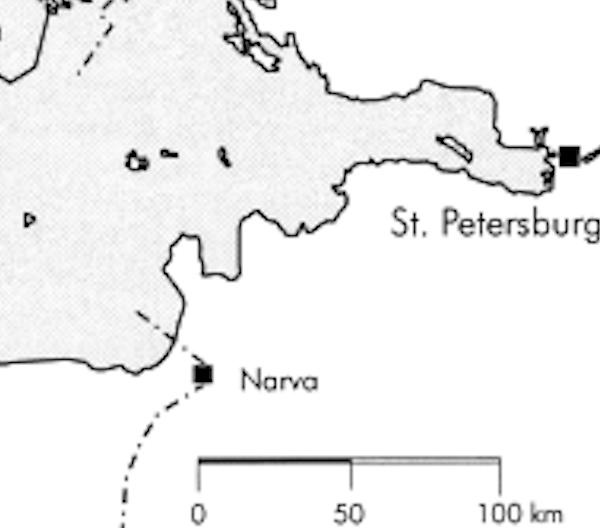

Vitino remained unsafe, the options were to go east to contacts in nearby Leningrad or west towards Narva, 100km away.

On the road to Leningrad the family were met by refugees who had managed to escape the German seige of the city. That left the family with no choice other than to go west to Narva. To prepare the family returned to the forest hideout. Here they managed to live undiscovered for two weeks just miles from the front with Russian forces losing ground and destroying everything they left behind.

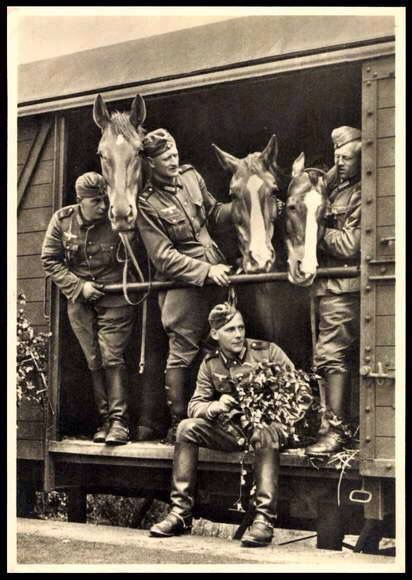

Albert recalled a morning in hiding that stayed fixed in his memory. He and his sisters had been woken early by his mother, told to be quiet and to stand outside. They were clearly being watched from the embankment above. Silhouetted and silent, figures stood still and couldn't be identified. Anxious about a Russian reprisal for ignoring the order to leave the family were relieved that the oncoming soldiers were a mix of Germans and Estonians.

Estonian troopers left a positive impression on Albert. In simple terms to be anti-Stalin necessitated being pro-German. He would have had no knowledge of the atrocities committed by 'SS Einsatzgruppe A' in Estonia.

By mid-March 1942 fighting had eased: German troops had taken over most of the area although Russsian aircraft continued attacking German positions.

In an eerie setting all buildings in the area were damaged but standing aloft and alone was a deserted manor house in which the two parents and seven children took refuge.

With some idea of the route to Narva the family prepared for their long trek.

Albert was particularly adept with horses and took responsibility for ensuring it had time to graze and recover. Early on the morning of the 22nd March 1942 after harnessing the horse the wagon was loaded, with space for the three youngest. The destination was Narva, the Estonian border town.

The journey took four days. Vassili was ever-alert choosing safe overnight roadside stops but meagre rations left the under-nourished family, weak, and tired.

Aliide maintained a constant vigilance over the children whilst Albert encouraged the ailing horse to cover about 25km per day.

For most refugees the regular German army presented few problems aware that they were escaping Soviet repression and within their number were new recruits.

The German army ended the brutal years of Soviet occupation of Estonia. The German occupation (1941 to 1944) was at first welcomed by Estonians

The Georgijevs crossed the border at Narva on the 25th March 1942. Given their unhealthy state, both physically and mentally, the children were immediately quarantined, deloused, bathed and fed.

All managed to physically recover from the ordeal, all except Aliide. After weeks of suffering with typhus fever her body eventually succumbed. She died at 6.45am on 24 May 1942, on Pentecost, in Narva hospital, 'a terrible loss for the family' (Salme).

Relatives were united for the funeral, and to add to their discomfort they would have witnessed heavy rain flooding the grave.

Heavy stones had to be used to weigh down the coffin. An ignominious ending for Aliide, a dedicated mother, a devout christian, a figure of dignity.

The Georgijev Family, May 1942, Estonia

- Vassili 52 years old

- Rosalie, 22y

- Ludmilla, 21y

- Albert, 18y

- Salme, 16y

- Nina, 13y

- Leontina (Lonni), 10y

- Maria (Manni), 6y

Aliide's death left the children without a mother. The youngest three girls Nina, Leontina (Lonni), and Maria (Manni) still needed a mother figure. It would have been customary to split them up between different relatives even though they were not familiar to the girls. However, Salme, just 16, stepped forward and accepted the role in order to keep the sisters together.

Eighty four years after her death Aliide's story, Salme's selflessness, and the fortitude of Vassili is remembered here. Albert's story continues.